According to certain parties with a stake in the telling of Indian history, most if not all of the problems India has experienced can be blamed on Brāhmins:

Anti-Brāhmin ideologues routinely assign collective blame to Brāhmins, usually to the effect that Brāhmins oppress, obstruct, or exploit others. They argue that Brāhmins authored the various Hindu scriptures for their own selfish benefit, to secure their alleged privilege and position at the expense of everyone else.

Many Brāhmins educated in the Western tradition have even internalized this criticism. Instead of questioning its validity, some of them issue profuse apologetics for imaginary offenses that they were never a party to. Others take the role of collaborators with the Western academic narrative, publicly reinforcing the anti-Brāhmin bias to demonstrate their liberal bona fides:

This is the underlying premise in both cases. Brāhmins traditionally lacked empathy and compassion, and they were obsessed with only protecting their power and prestige even if it meant harming everyone else to do it.

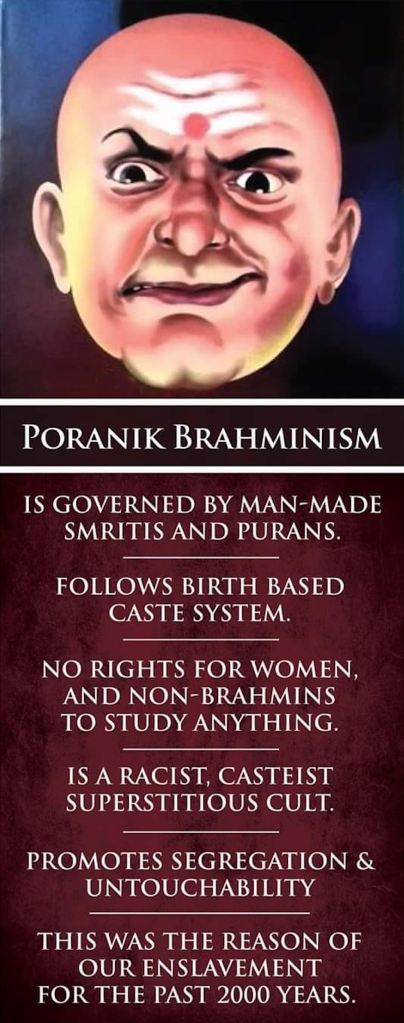

This is evidenced by Exhibit A1 below, part of a propaganda meme found on social media (before it was taken down) which alleges the existence of “Poranik Brahminism” which is different from “Vedic Dharma.”

The meme’s author, a follower of the revisionist, neo-Hindu, Arya Samaj, holds that the “Man-Made Smritis and Purans” (meaning, the Mahābhārata, Rāmāyaṇa, and the Purāṇas) created a sinister spectre of Brāhmin culture which allegedly promotes racism, casteism, sexism, segregation, untouchability, and “was the reason for our enslavement for the past 2000 years.” It should be noted that historically, Brāhmins never “enslaved” anyone; slavery was an institution that came with Islam and the British. Nevertheless, the caricatured Brāhmin having dark eyebrows, widely open eyes, near-black pupils, sharply accentuated features, and a maniacal half-smile reinforces the image of malicious sadism. The idea conveyed is that Brāhmins are evil people who derive sheer joy from enslaving and oppressing others.

Now consider Exhibit A2, the cover of a book published by Harvard University Press regarding “the social life of caste in India.”

The original tweet can be found here, and as one can see, Harvard was embarrassed into taking the original cover down after protests from the Hindu community. The original cover seen above depicts a shaven-headed, saffron-wearing Brāhmin, taking the help of a demonic-appearing skeleton to engage in some kind of religious ritual that involves torturing dark-skinned people, evidently here representing “lower caste” Hindus.

Once again, the salient concept is the traditionally attired Brāhmin as an agent of oppression. This imagery is considered innocent, inoffensive, and appropriate for use in the halls of American academia… as long as no one protests.

Now consider Exhibit B which most humane individuals including the creators of the images A1 and A2, would certainly regard as atrocious:

This German propaganda painting circa 1942 (courtesy of the Holocaust Encyclopedia) depicts a Jewish man with black clothes, thick eyebrows, a fat nose, a coarse & ugly face, and a sly, sinister look. The caption in German reads, “Behind the enemy powers: the Jew.” Similar to Brāhmins who are regarded as a cultural elite in India, the Jews of pre-World-War-2 Germany were an economically prosperous minority community, making them (like the Brāhmins) a convenient target. Like the other two memes about Brāhmins, this painting ascribes impure motives to an entire group of individuals and encourages revulsion against them based on their cultural identity.

The fact that Exhibit B and others like it were used to justify mass murder should give us pause. Do negative and dehumanizing portrayals of minority groups put them at risk for vigilante or government-sponsored violence? Based on the lessons of history, most thoughtful, objective people would agree that it does. Yet many of those people forget that Brāhmins are also a minority, constituting no more than 4-5% of the population of India. During 900 years of Islamic invasions and occupation of India, Brāhmins, being the spiritual leaders of their communities, were specifically targeted by the Islamic faithful for conversion or execution. Anti-Brāhmin violence persisted even after Indian independence. In 1948, the Chitpavan Brāhmin community of Maharashtra was targeted for genocide by political opponents, leaving up to 8,000 dead. During 1989-1990, around 400,000 Kashmiri Pandits were ethnically cleansed from their ancestral homelands by Islamic radicals with hardly any international outcry against it. Targeted killings of Brāhmins continue to the present day. This being the case, one might reasonably wonder, “What significant difference exists between the mindsets of those who promote revulsion of Brāhmins as opposed to those who promote revulsion against Jews?” After all, both of them employ the same strategy of insinuating guilt based solely on membership within socioreligious groups.

Now critics of Brāhmins may protest that this comparison is unfounded. They might hold that unlike Jews, Brāhmins are collectively guilty of oppressing members of other castes. In this context, let us consider Exhibit C, an article on caste-related violence in India from Wikipedia, annotated with 81 linked references to various journalistic and scholarly media on the subject. This article lists 34 episodes of caste-based violence in India including details of both the perpetrators and their victims. A summary of its findings is given below:

| Event | Perpetrators | Victims | Rationale, Notes |

| 1948 Maharashtra Anti-Brahmin “Riots” (others say pre-planned genocide) | Kunbi Marathas | Chitpavan Brahmins | Assassination of Gandhi by a Brahmin, though other sources claim Congress Party political motivations |

| 1987 Dalelchak-Bhagora massacre | Maoist communists | 52 “upper caste” members mostly from Rajput community | Revenge for killings by militant “upper caste” organizations |

| 1968 Kilvenmani massacre | Unspecified | Dalits village laborers | Landlord reprisal because Dalits demanding higher wages |

| 1981 Abduction & rape of Phoolan Devi | Thakurs | Phoolan Devi, member of boatman class Mallaah family | ? |

| Phoolan Devi | Poolan Devi & her gang of Mallahs | 22 Thakur men | Reprisal for rape by a Thakur man, though only two of the 22 were alleged to have been involved. Before her assassination, Phoolan Devi would later be elected to parliament |

| Assassination of Phoolan Devi | Sher Singh Rana | Phoolan Devi | Revenge for the death of the 22 Thakurs mentioned above. Perpetrator imprisoned but escaped from jail, later honored by his community for the act |

| 1985 Karamchedu massacre | Kammas | Madiga caste Dalits | ? |

| 1990s Ranvir Sena | “higher caste landlords” | Naxals, Dalits, other scheduled castes | “in an effort to prevent their land from going to them” |

| 1991 Tsundur, Andhra Pradesh | 300+ person mob, mainly Reddys & Telagas | 8 Dalits | Evidently a reprisal for locals being asked to “go aggressive against large number of eve-teasing outsiders entering the village.” 21 perpetrators sentenced to life imprisonment. |

| 1992 Bara Massacre, Bihar | Maoist Community Centre of India | 35 members of Bhumihar Brahmin caste | Likely inspired by communist class-conflict ideology. 36 people accused of the crime, charges only framed against 13, others not arrested as they defied their summons |

| 1996 Bathani Tola Massacre, Bihar | Ranvir Sena, a “far-right-wing caste-based militia functioning as an upper caste landlord group” | 21 Dalits including 11 women and 6 children & possibly 6 Muslims including a 3-month-old infant. A 7-year-old child’s face was mutilated by lacerations | “The land is ours. The crops belong to us. The labourers did not want to work, and also hampered our efforts by burning our marchines and imposing economic blockades. So, they had it coming.” 23 men were convicted of the murders, but later acquitted due to “defective evidence” |

| Post Bathani Tola attacks | Naxalites | “at least 500 upper caste civilians” | Presumably a reprisal for the Bathani Tola massacre |

| Post Bathani Tola attacks | Ranvir Sena | 81 Dalits | Presumably reprisals to Naxalite attacks |

| 1994 Chhotan Shukla murder case | Followers of Brij Bihari Prasad, a minister from the Bania caste | Chhotan Shukla, “a gangster of the Bhumihar (Brahmin) community” | Political differences |

| Retribution for Chhotan Shukla murder | Rajput leader Mohan Singh and Bhumihar Brahmin Munna Shukla | Brij Bihari Prasad, from the OBC Bania caste | Revenge for Chhotan Shukla murder, Both perpetrators tried and given life imprisonment |

| Retribution for Chhotan Shukla murder | “by upper castes” | District Magistrate of Gopalanj G. Krishnaiah | “he symbolized the growing power of backwards (castes).” |

| 1996 Melavalavu murders | Kallar-caste | six Dalits | Election of a Dalit to village council presidency after the constituency was declared a reserved constituency in 1996 creating tensions between the communities. Total of 40 people accused, 17 convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment |

| 1997 Laxmanpur Bathe Carnage, Bihar | Ranvir Sena | 58 Dalits | Retaliation for the Bara massacre in Gaya. 46 Ranvir Sena men charged, 26 convicted, and 16 sentenced to death while 10 more sentenced to life imprisonment. However, 26 convicts later acquitted for unclear reasons |

| 1997 Ramabai killings, Mumbai | Mumbai police | Protesters were protesting the defacing of a B.R. Ambedkar status in the Dalit colony of Ramabai, 10 people killed in a police shooting, then later 26 more injured by a police lathi charge | Possibly caste-based prejudice on the part of the police team leader |

| 1999 Senari Massacre | Maoists | 34 Bhumihar Brahmins | unspecified |

| January 1999 Ramvati devi case, Punjab | four members of village panchayat of Bhungar Khera village, castes unspecified | a handicapped Dalit woman was paraded naked through the village | No action taken by police despite Dalit protests until July 1999 when the perpetrators were finally arrested |

| 2006 Bant Singh case, Punjab | unknown assailants | Bant Sing, Mazhabi, Dalit Sikh – Dalits | alleged to be retaliation for working to secure justice for Ramvati devi |

| 2007 Sawinder Kaur case | not specified, possibly members of the “upper caste” community whose members were involved in the Ramvati devi case | Dalit Sikh woman was tortured, stripped, and tied to a tree | Her nephew eloped with a girl from the “same community,” possibly referring to the “upper caste” community responsible for the humiliation of Ramvati devi. Four persons arrested. |

| 2000 Afsar Nawada killings | Ashok mahto gang formed by a koeri-caste militant who was also responsible for atrocities against “upper castes” | “a score of people” from Bhumihar Brahmin community | “rivalry for domination between upper caste bhumihar (Brahmin) and upper backward castes koeri and kurmi” |

| 2000 Kambalapalli incident, Karnataka | Reddy mob | Seven Dalits locked in a house and burned alive | “deep-rooted animosity between the Dalits and the upper-castes.” 46 were accused, but Karnataka High Court acquitted all 46 accused because 14 years had passed and all 22 eyewitnesses “had since turned hostile,” other investigative abnormalities. |

| 2003 Muthanga incident, Kerala | Police | Adivasis (tribals) subjected to 18 rounds of police firing, 5 killed including a police constable who was also a Dalit | Protest against government delay in allotting them land which was agreed upon in 2001 |

| 2005 Jahanabad prison raid | Maoists, “low-caste” agricultural laborers led by poor peasants of “upper backward castes” like keori and teli | Ranvir Sena prisoners of the district prison | Not specified, likely ongoing caste-rivalry and conflict as outlined previously |

| 2006 Khairlanji massacre, Maharashtra | Mob of 40 people belonging to Maratha Kunbi caste | four members of the Botmange family belonging to the Mahar (Dalit) community | Victims stripped naked and paraded to the village, sons were ordered to rape their mothers/sisters, their genitals mutilated and then they were murdered when they refused. Due to police delays, much of evidence destroyed. 8 People eventually sentenced to life imprisonment by Bombay High Court which declared the the murders were motivated by revenge, not caste. |

| 2006 Dalit protests in Maharashtra | Dalit protestors | Four deaths and many more injuries after Dalits set three trains on fire, damaged 100 buses, and clashed with police | Desecration of a B.R. Ambedkar statue |

| 1999-2002 Rajasthan crimes against Dalits | not specified | Approximately 5024 crimes against Dalits between 1999 and 2002 with 46 killings and 138 cases of rape | not specified |

| 2008-2010 Gurjar agitation in Rajasthan | Both Gurjars (a farming and trading community) and police were alternatingly victims and perpetrators in a variety of incidents starting with Gurjar demands for special status | ||

| 2011 killings of Dalits in Mirchpur, Haryana | Jats | Dalits | A Dalit’s dog barked at some drunken Jat boys, one of whom hurled a brick at the dog, leading to a fight between a Dalit and the Jat which escalated into conflicts culminating in the orchestrated burning down of Dalit houses by Jats with two fatalities and many more Dalits fleeing for safety. A total of 35 perpetrators were eventually convicted. |

| 2012 Dharmapuri violence | Vanniyar | Torching of 268 dwellings of Adi Dravida Dalits | |

| 2012 Dharmapuri violence | “Upper-caste” Muslims comprising Pathans and Sayyeds | Akbar Ali and Mustafa Ansari (“lower-caste” Pasmandas) | Election-related tensions |

| 2013 Marakkanam violence, Tamil Nadu | Vaniyyars | Dalits | Drunken Vaniyyar members of the Pattali Makkal Katchi party assaulted local Dalit villagers who then killed two Vaniyyars. |

| 2015 Dalit violence in Dangawas, Rajasthan | Jats and Dalits clashed resulting in 4 deaths and 13 injuries | ||

| 2016 Rohith Vemula suicide | Half-dalit, half-Vaddera Rohith Vemula committed suicide after being suspended from the University of Hyderabad after assaulting a right-wing ABVP party leader, this after the university stopped paying his PhD stipend 1 month prior due to “paper work” (allegedly this was due to political reasons) | ||

| 2016 Gang-rape and murder of Nandini, Tamil Nadu | castes not specified, perpetrators were mbmers of the Hindu Munnani | 17-year-old Dalit girl | Reportedly the girl was pregnant with child of the Hindu Munnani Union Secretary who became irriated over her insistence that he marry her |

| 2017 Anandpal Singh murder case | Jats & Rajputs | Jats & Rajputs | This was a culmination of battles for dominance between Jats and Rajputs of Rajasthan. Rajput Anandpal Singh was allegedly involved in the murder of several Jats and was subsequently murdered as well |

| 2017 Saharanpur violence | unclear | Dalits | “The violence broke out during the procession of Rajput warrior-king Maharana Pratap over the loud music. In the violence one man was killed, 16 were injured and 25 Dalit houses were burned. The incident was connected to the BJP MP from Saharanpur Raghav Lakhanpal.” |

| 2018 Samrau violence in Jodhpur, Rajasthan | Jats and Rajputs | Jats and Rajputs | “On the evening of 14 January 2018, clashes between Jats and Rajputs in Samrau village of Rajasthan’s Jodhpur district burned shops and houses of many innocent people, and destroyed the Rawla (king’s residence).” |

| January 2018 Stone pelting at Bhima Koregaon, Maharashtra | Conflicting reports indicate Peshwas, right-wing Hindu groups, or Maoists | “Depressed classes” including Mahars | There were clashes between Peshwas vs “Depressed Classes” (which includes Mahars) regarding the history surrounding a statue commemorating the 1818 Battle of Koregaon |

| April 2018 caste protests | Schedule Castes and Scheduled Tribes | police, public property, other civilians | The protest was against a Supreme Court order that allowed courts to grant anticipatory bail to arrested suspects if it found the complaint against them to be an abuse of the law. SC/ST members staged violent protests |

| May 2018 temple incident in Kachanatham, Sivagangai, Tamil Nadu | 15 “Dominant caste Hindus” | 3 Dalits fatalities and 6 Dalit injuries | “Dominant caste Hindus were “enraged” that Dalits did not present temple honours to an upper-caste family, and a Dalit man sat cross-legged in front of upper-caste men. Dominant caste members also were enraged when Dalits protested the sale of marijuana in the area by people from a neighbouring village and intimidated and threatened the Dalits.” |

| 2019 suicide of Dr. Payal Tadvi | three “upper caste” women doctors | scheduled tribe gynecologist | “a 26-year-old Schedule Tribe gynaecologist, died by committing suicide in Mumbai. For months leading up to her death, she had told her family that she was subjected to ragging by three “upper” caste women doctors. However, the accused denied having any knowledge of Dr Payal’s tribal background. They allegedly went to the toilet and then wiped their feet on her bed, called her casteist slurs, made fun of her for being a tribal on WhatsApp groups and threatened to not allow her to enter operation theatres or perform deliveries.” |

The vast majority of caste violence in India was perpetrated by non-Brāhmins against other non-Brāhmins. Of the 45 episodes listed, there is only one confirmed case of a Brāhmin perpetrating caste violence, and even this episode appears to be based on revenge rather than caste. On the other hand, Brāhmins were more often victims in caste-based violence, with five of the documented episodes involving the targeting of Brāhmins. Even this analysis does not include the horrific 1989-1990 ethnic cleansing of Kashmiri Pandits.

Dalits were frequently targets of caste violence, but not by Brāhmins, and sometimes Dalits were themselves instigators of caste violence, including violence directed against Brāhmins. Every documented episode of caste violence occurred *outside* the sphere of orthodox Hindu practice, without invoking any Hindu principle as justification, and were often based on land disputes, protests against government policy, or local rivalries that had no basis in religion. Thus, the argument that Brāhmins were historically oppressive to other castes, and that such oppression was inspired by Hinduism, is contradicted by an objective appraisal of the historical evidence.

Leftist academics, anti-Hindu ideologues, and some neo-Hindu revisionists frequently assert that the śāstras were authored by Brāhmins to jealously secure their social status, “privilege,” and dominion over other Hindus (see Exhibit A1 above). But is this view rational? One would expect selfishly-engineered religious texts to emphasize overriding principles about social hierarchy, such as the divine right of a ruling class to dominate others. Yet the actual statements from these texts contradict that view, emphasizing an equality that underlies all social hierarchy:

विद्याविनयसंपन्ने ब्राह्मणे गवि हस्तिनि ।

(Bhagavad-gītā 5.18) [translated by Swami Adidevananda]

शुनि चैव श्वपाके च पण्डिताः समदर्शिनः ॥ गीता ५.१८ ॥

“The sages look with an equal eye on one endowed with learning and humility, a Brāhmaṇa, a cow, an elephant, a dog and a dog-eater.”

This illustrates the well-known, Hindu view that the self is not the body, and therefore the distinctions pertaining to the body (such as sex, varṇa, and caste) are temporary and not intrinsic to one’s actual identity. Thus, a Hindu with this knowledge sees himself in the bodies of others:

सर्वभूतस्थमात्मानं सर्वभूतानि चात्मनि ।

(Bhagavad-gītā 6.29) [translated by Swami Adidevananda]

ईक्षते योगयुक्तात्मा सर्वत्र समदर्शनः ॥ गीता ६.२९ ॥

“He whose mind is fixed in Yoga sees equality everywhere; he sees his self as abiding in all beings and all beings in his self.”

In other words, seeing the underlying equality of other living beings, he recognizes that the living being in another body, even a body he might perceive as despicable and low, could be him in his next life:

शूद्रयोनौ हि जातस्य सहगुणानुपतिष्ठतः ।

(Mahābhārata 3.212.11-12) [translated by M.N. Dutt]

वैश्यत्वं लभते ब्रह्मन् क्षत्रियत्वं तथैव च ॥ महा ३.२१२.२१ ॥

आर्जवे वर्तमानस्य ब्राह्मण्यमभिजायते ।

गुणास्ते कीरतिताः सर्वे किं भूयः श्रोतुमिच्छसि ॥ महा ३.२१२.१२ ॥

“O Brāhmaṇa, a man may be born as a Śūdra but if he is endowed with good qualities, he may attain to the state of a Vaiśya. Similarly that of a Kṣatriya and if he is steadfast in rectitude he may even become a Brāhmaṇa. I have described to you all these virtues, what else do you wish to learn?”

Because the self reincarnates into different varṇas, the Hindu concept of varṇa identity is obviously fluid, not static. Instead of encouraging caste-based oppression, a fluid varṇa identity rationalizes an appreciation for everyone’s shared identity as equal ātmans transcending differences of birth. This mandates compassion and concern for the welfare of all living beings, attributes which are repeatedly described as a required practice for Hindus:

आनृशंस्यं परो धर्मस् ॥ महा ३.३१३.७६ ॥

(Mahābhārata 3.313.76) [translated by M.N. Dutt]

“Absence of cruelty is the highest virtue…”

न हीदृशं संवननं त्रिषु लोकेषु विद्यते ।

(Mahābhārata 1.87.12-13) [translated by M.N. Dutt]

दया मैत्री च भूतेषु दानं च मधुरा च वाक् ॥ महा १.८७.१२ ॥

तस्मात् सान्त्वं सदा वाच्यं न वाच्यं परुषं क्वचित् ।

पूज्यान् सम्पूजयेद् दाद्यान्न च याचेत् कदाचन ॥ महा १.८७.१३ ॥

“There is nothing in the three worlds with which you can worship the deities as kindness, friendship, charity and sweet words. Therefore, you should always utter sweet words that give pleasure and not pain. You should always give and never beg. You should show respects to those that deserve your respect.”

दीनानामनुकम्पया ॥ भा.पु. ३.२९.१७ ॥

(Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa 3.29.17) [translated by Ganesh Tagare]

“(The mind of my devotee becomes purified) by showing compassion to the afflicted…”

The practice of universal compassion is not just a matter of duty. The scriptures indicate that it is also exhibited naturally by enlightened people:

लभन्ते ब्रह्मनिर्वाणमृषयः क्षीणकल्मषाः ।

छिन्नद्वैधा यतात्मानः सर्वभूतहिते रताः ॥ गीता ५.२५ ॥“The sages who are free from the pairs of opposites, whose minds are well subdued and who are devoted to the welfare of all beings, become cleaned of all impurities and attain the bliss of Brahman.”

(Bhagavad-gītā 5.25) [translated by Swami Adidevananda]

शिवाय लोकस्य भवाय भूतये य उत्तमश्लोकपरायणा जनाः ॥ भा.पु. १.४.१२ ॥

(Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa 1.4.12) [translated by Ganesh Tagare]

“The persons who are devoted to Lord Viṣṇu live for the happiness, abundance, and prosperity of others and not for themselves.”

The evidence from scriptures, alleged to have been authored by Brāhmins for their own selfish benefit, shows that Brāhmins had no religious justification for oppressive behavior. A world-view that emphasizes spiritual equality and compassion for all living beings is the polar opposite of the “racist, casteist, superstitious cult” that the Arya Samaj makes it out to be.

Unlike most caste systems, the varṇāśrama system was never about preserving hierarchy for its own sake. It’s purpose was to identify the duties (sva-dharma) one should selflessly perform as a form of worship:

वर्णाश्रमाचारवता पुरुषेण परः पुमान् ।व

(Viṣṇu Purāṇa 3.8.9)

िष्णुराराध्यते पन्था नान्यस्तत्तोषकारकः ॥ वि.प. ३.८.९ ॥

“The supreme Viṣṇu is propitiated by a man who observes the institutions of varṇa, āśrama, and purificatory practices; no other path is the way to please Him.”

स्वे स्वे कर्मण्यभिरत: संसिद्धिं लभते नर ।

(Bhagavad-gītā 18.45-46) [translated by Swami Adidevananda]

स्वकर्मनिरत: सिद्धिं यथा विन्दति तच्छृणु ॥ गीता १८.४५ ॥

यत: प्रवृत्तिर्भूतानां येन सर्वमिदं ततम् ।

स्वकर्मणा तमभ्यर्च्य सिद्धिं विन्दति मानव: ॥ गीता १८.४६ ॥

“Devoted to his duty, man attains perfection. Hear now how one devoted to his own duty attains perfection. He from Whom arise the activity of all beings and by Whom all this is pervaded – by worshiping Him with his own duty man reaches perfection.”

This worship of God through action and duty is known as karma-yoga, which Hinduism regards as a practical and joyful alternative to the ascetic tradition. Ambiguity about one’s duties is not an issue precisely because of the varṇa system. That varṇa duties are ONLY for the worship of Bhagavān and not for any other purpose (such as guarding social privilege) is explicitly stated:

धर्मः स्वनुष्ठितः पुंसां विष्वक्सेनकथासु यः ।

(Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa 1.2.8) [translated by Ganesh Tagare]

नोत्पादयेद्यदि रतिं श्रम एव हि केवलम् ॥ भा.पु. १.२.८ ॥

“A dharma well performed is but labor lost, if it fails to generate love for the stories of Bhagavān Viṣvaksena (Śrī Kṛṣṇa).”

Here, then, is the basic difference of thinking between traditional Hindu thinkers and foreign academics. Foreign academics, whose imagination has been colored by Marxist theories of class-conflict, insist that varṇāśrama-dharma is a “caste-system” designed to allow a privileged few to live off of the toils of others. But varṇāśrama-dharma according to Hindu scripture is a personal, voluntary, spiritual practice in which a Hindu worships God through his work. In other hereditary social systems, it was no coincidence that the highest classes were nobles who enjoyed the greatest wealth, power, and prestige. But in the varṇa system, the highest position was that of the poor Brāhmin whose only wealth was his knowledge, austerity, and saintly devotion. The respect he was given reflected the values of Hindu civilization, which placed a greater premium on spirituality than on material possessions.

That a Brāhmin was expected to be a spiritual exemplar is clearly understood from the very same smṛti texts that he was alleged to have authored to secure his “privilege.”

युधिष्ठिर उवाच

(Mahābhārata 3.180.21) [translated by M.N. Dutt]

सत्यं दानं क्षमा शीलमानृशंस्यं तपो घृणा ।

दृश्यन्ते यत्र नागेन्द्र स ब्राह्मण इति समृतः ॥ महा ३.१८०.२१ ॥

“Yudhiṣṭhira said: ‘O monarch of snakes, it is said that he is a brāhmaṇa in whom are found (the qualities of) truthfulness, charity, forgiveness, good conduct, benevolence, asceticism and mercy.’”

धर्मश्च सत्यं च दमस्तपश्च अमात्सर्यं ह्रीस्तितिक्षानसूया ।

(Mahābhārata 5.43.10) [translated by M.N. Dutt]

यज्ञश्च दानं च धृतिः श्रुतं च व्रतानि वै द्वादश ब्राह्मणस्य ॥ महा ५.४३.२० ॥

“Righteousness, truthfulness, self-control, asceticism, delight at other’s happiness, modesty, forgiveness, reverse of malice, performance of sacrificial ceremonies, gifts, patience, learning and vows, these twelve are the attributes of a brāhmaṇa.”

शमो दमस्तपः शौचं सन्तोषः क्षान्तिरार्जवम् ।

(Śrīmad Bhāgavatam 7.11.21) [translated by Ganesh Tagare]

ज्ञानं दयाच्युतात्मत्वं सत्यं च ब्रह्मलक्षणम् ॥ भा.पु. ७.११.२१ ॥

“Control over mind and senses, asceticism, purity, contentment, forbearance and forgiveness, straightforwardness, knowledge, compassion, fervent devotion to Lord Viṣṇu and truthfulness are the characteristics of a Brāhmaṇa.”

If one wanted to create religious books to selfishly guard one’s social status, one could hardly find a more counter-productive way of doing it than to mandate virtue and austerity in those very same books. The absurdity of this contradiction was also noted by Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Swami of the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham:

“It is alleged that Brāhmins created the dharma-śāstras for their own benefit. You will realize that this charge is utterly baseless if you appreciate the fact that these śāstras impose on them the most stringent rules of life. There is also proof of the impartiality of the dharma-śāstras in that the Brāhmin who is expected to be proficient in all the arts and all branches of learning can only give instruction in them but cannot take up any for his livelihood however lucrative it be and however less demanding than the pursuit of the Vedic dharma.”

http://www.kamakoti.org/hindudharma/part20/chap10.htm

Not only do Brāhmins have the most stringent rules imposed on them by the scriptures, but those same scriptures explicitly invalidate birth as an independent basis for social acceptance:

न कुलं वृत्तहीनस्य प्रमाणमिति मे मतिः ।

(Mahābhārata 5.34.41) [translated by M.N. Dutt]

अन्तेष्वपि हि जातानां वृत्तमेव विशिष्यते ॥ महा ५.३४.४१ ॥

“It is my opinion that noble birth in one who is not of good behaviors does not mean virtue; and that good manners in one born low should command respect.”

लौकायतिकान्ब्राह्मणांस्तात सेवसे ।

(Vālmīki-Rāmāyaṇa 2.100.38-39) [translated by P. Geervani, K. Kamala, and V.V. Subba Rao]

अनर्थकुशला ह्येते बालाः पण्डितमानिनः ॥ वा.रा. २.१००.३८ ॥

धर्मशास्त्रेषु मुख्येषु विद्यमानेषु दुर्बुधाः ।

बुद्धिमान्वीक्षिकीं प्राप्य निरर्थं प्रवदन्ति ते ॥ वा.रा. २.१००.३९ ॥

“Dear brother, I hope you do not serve those brāhmins who are atheists, who foolishly think of this world alone and fancy themselves as learned. They only bring disasters. While principal scriptures do exist, these superficial fellows take resort to the science of logic based on abstract reasoning, and indulge in futile talks.”

गृहस्थस्य क्रियात्यागो व्रतत्यागो वटोरपि ।

(Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa 7.15.38-39) [translated by Ganesh Tagare]

तपस्विनो ग्रामसेवा भिक्षोरिन्द्रियलोलता ॥ भा.पु. ७.१५.३८ ॥

आश्रमापसदा ह्येते खल्वाश्रमविडम्बनाः ।

देवमायाविमूढांस्तानुपेक्षेतानुकम्पया ॥ भा.पु. ७.१५.३९ ॥

“Avoidance of religious rites and duties in the case of gṛhastha, non-observance (of the vow of celibacy, studies etc.) in the case of a brahmacārin, residence in an inhabited locality in the case of ascetics performing penance, and lack of self-control in the case of recluses (saṁnyāsins) – all these are the accursed banes of their respective āśramas as these certainly reduce their āśramas to mockery. Out of compassion, one should neglect these fellows who are deluded by the illusive power (Māyā) of the Almighty God.”

When conduct and birth are discordant, the smṛtis explicitly downplay the significance of birth in favor of virtuous conduct. This contradicts the narrative that Brāhmin birth guarantees “privilege.” The point here is not that birth does not determine varṇa. Rather, the point is that a Brāhmin who doesn’t hold firm to brāhmin virtues is not to be blindly respected or followed. This point is made clearly when Rāma advises Bharata not to support worldly, atheistic Brāhmins, or when Nārada advises Yudhiṣṭhira to ignore those Brāhmins who neglect their religious duties. If Brāhmins authored these texts to selfishly guard their status, they should have instead stressed the overriding sanctity of their birth over moral conduct.

Not only do the smṛtis advise Hindus to ignore wayward Brāhmins of respectable birth, they also venerate Viṣṇu-devotees born from the humblest of communities:

संस्मृतः कीर्तितो वापि दृष्टः स्पृष्टोऽपि वा प्रिये ।

(Varāha Purāṇa 211.91) [translated by A Board of Scholars, edited by J.L. Shastri]

पुनाति भगवद्भक्तश्चाण्डालोऽपि यदृच्छ्या ॥ व.पु. २११.९१ ॥

“If a devotee of Viṣṇu, even though he be a Caṇḍāla, is recollected, named, seen or touched accidentally by anybody, O dear madam, the former purifies them.”

To understand the significance of this statement, one must understand that Caṇḍālas were born outside of varṇāśrama society and were generally thought to have base habits such as eating of dogs. But in spite of this, the texts are quite clear that Viṣṇu-bhakti redeems them, even making them auspicious and purifying to all others:

विप्राद्द्विषड्गुणयुतादरविन्दनाभ पादारविन्दविमुखात्श्वपचं वरिष्ठम् ।

(Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa 7.9.10) [translated by C.L. Goswami]

मन्ये तदर्पितमनोवचनेहितार्थ प्राणं पुनाति स कुलं न तु भूरिमानः ॥ भा.पु. ७.९.१० ॥

“I account a pariah (a Caṇḍāla) – who has dedicated his mind, speech, actions, wealth and life (itself) to Him – far worthier than a Brāhmaṇa that has turned away his face from (the worship of) the lotus-feet of Lord Viṣṇu (which has a lotus sprung from His navel), though endowed with the (aforesaid) twelve attributes. (For) the former redeems his (whole) race, but not the Brāhmaṇa, (who is) full of inordinate pride (and therefore unable to redeem his own soul, much less his race).”

The dismissive attitude towards Brāhmaṇas who don’t live up to the brāhminical standard is very clear from the texts. A “Brāhmin” is etymologically understood to be one who understands and reveres Brahman, and Brahman is explicitly identified as Viṣṇu in the sacred texts of Hinduism. Thus, birth is not an actual measure of greatness; only Viṣṇu-bhakti is. Such is the significance of Viṣṇu-bhakti and its universal appeal, that it raises a Caṇḍāla to greatness while its absence degrades even a Brāhmin of respectable birth. The fact that its scriptures place a greater value on bhakti over birth contradicts the theory that Hinduism endorses “caste privilege.”

This principle of uplifting the sinful and the disadvantaged and welcoming them into the community of devotees was not merely a theoretical one. It was actually the practice of orthodox, brāhmin, spiritual leaders for many centuries:

“Śrī Rāmānujācārya Swamy decided to go to Delhi to retrieve the vigraha. The king too wanted to come with all his military strength to aid Swamy to reclaim the vigraha. Śrī Rāmānujācārya Swamy said that he did not want to display any physical prowess. He was certain that the Lord will aid him in his efforts. The upper caste people were uncomfortable to accompany Śrī Rāmānujācārya Swamy to the impure land of mlecchas, but the rest unhesitatingly and unconditionally followed him to Delhi, To recognize this, Śrī Rāmānujācārya Swamy later created for them the position of kombina chelva – the one who heralds the starting ceremony of the Perumāl thiruvīdhi or the street procession. The custom is still followed even today.

H.H. Chinna Jeeyar Swamij, A Short Biography of Sri Ramanujacharya Swamy, p 101, 105

Śrī Rāmānujācārya Swamy worked hard to uplift the downtrodden people, many of whom had followed him to Delhi to get Sampathkumāra back from the Sultan. He gave them pañca saṁskāram, taught them rules and regulations to live a disciplined and fulfilling life, enabled them to see the Lord in the temple, and gave them an honorable place in society. He called them Thirukkulaththār. Thus, he addressed the unhealthy practice of untouchability and reintegrated them into the reformed society.”

Notably, Śrī Rāmānuja (1017–1137 C.E.) was himself a follower of the traditional, heredity-based varṇa culture. Despite being a Brāhmin, he had a śūdra mentor during his youth whom he respected as a great Vaiṣṇava.

Another orthodox Brāhmin exhibiting Hinduism’s inclusive social ethic was Purandara dāsa (1484 – 1565 C.E.). A follower of the Mādhva sampradāya of Vedānta, Purandra dāsa was renowned as the grandfather of Carnatic music and himself used devotional songs mostly written in the vernacular to communicate the teachings of Hindu scripture to the common people. Regarding his views on caste and untouchability, it was said that:

“Purandara Dasa made some forceful expressions on untouchability, which was dogging society. His strength comes perhaps from the support of his guru Vyasathirtha with the backing of powerful king Krishnadevaraya of Vijayanagara himself. In one such song Holaya horagithane oorolagillave he opines that an individual should not be branded untouchable on the basis of his/her birth in any specific caste, however it is rather his conduct which should make him untouchable if at all he can be called so. The usage of the word untouchable is not used in the limited context of physical contact with the person, it is the worthlessness of the association with that person which is highlighted here. This is evident by the subsequent expressions in the song which says that one who does not practice self-discipline is untouchable, one who plots against his own government is untouchable, similarly one who shirks charity while having wealth is untouchable, one who poisons to eliminate his opponents is untouchable, one who does not use soft language is untouchable, one who prides over his purity of caste is untouchable and finally one who does not meditate on Purandara Vittala is untouchable. Dasa’s message is loud and clear rejecting untouchability in our society.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purandara_Dasa#Untouchability

Yet another example of Brāhminical outreach and inclusivity was that of Caitanya (1486 – 1533 C.E.), a 16th century Vaiṣṇava saint of Bengal. His principal biography indicates that, contrary to stereotypes of casteism and untouchability, he associated freely with non-Brāhmaṇa devotees:

“Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu then inquired whether he was Rāmānanda Rāya, and he replied, ‘Yes, I am Your very low servant, and I belong to the śūdra community.’ Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu then embraced Śrī Rāmānanda Rāya very firmly. Indeed, both the master and the servant almost lost consciousness due to ecstatic love. Their natural love for each other was awakened in them both, and they embraced and fell to the ground. When they embraced each other, ecstatic symptoms — paralysis, perspiration, tears, shivering, paleness and standing up of the bodily hairs — appeared. The word “Kṛṣṇa” came from their mouths falteringly.”

Śrī Caitaṇya Caritāmṛta, Madhya-līlā, 8.21.24, translated by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami

The actions and teachings of these orthodox, brāhmin, spiritual leaders illustrated how the Hindu worldview of transcendence and Viṣṇu-bhakti produced an inclusive social ethic based on a shared spirituality.

The tradition of bringing bhakti to such disadvantaged communities continues to the present day among orthodox, brāhmin leaders. The late Pejawar Swami of the Mādhva sampradāya had a habit of visiting Dalit communities to offer Vaiṣṇava initiation and speak out against atrocities committed against them. Mannargudi Jeeyar Swami, a Śrī Vaiṣṇava sannyāsi also regularly visits Dalit communities to conduct pūjās for them. Hailing from the same sampradāya, Chinnajeeyar Swami led efforts carried out by his brāhmin disciples to provide temple-style food for homeless people during the covid-19 lockdown. The head priest of Hyderabad’s Chilukuri Balaji Temple C.S. Rangarajan, who is so conservative that he objects to Hindus offering New Year greetings on January 1st, publicly observes a 2,700-year-old Hindu ritual in which he humbly brings Dalits on his own shoulders into the temple:

These acts of inclusiveness follow naturally from the Hindu worldview of equality of all souls and accessibility of Viṣṇu, the Supreme Puruṣa of the Vedas, to everyone.

A critic might argue that not every Brāhmin is so devoted and magnanimous, and some departing from Hindu scriptural norms were guilty of ignoble behavior. And in doing so, he would only prove our point. At the very least, Brāhmins are not privileged, casteist, oppressive, or exploitive as a group because, like all other human beings, they are not anything as a group. There is no such thing as collective guilt, because all individuals, including Brāhmins, should be judged on their individual merits.

The ongoing Hindu tradition of brāhmin outreach and compassion contradict the stereotype of Brāhmins as an oppressive, privileged, social elite. Hinduism is not built on caste privilege and oppression, but on an underlying unity in diversity centered around the shared worship of a Supreme God Who dwells within every living being. Despite the modern departure of many from the traditional Brāhmin lifestyle, history does not bear out the view that Brāhmins as a class were guilty of oppressing others. The very idea that this tiny, apolitical, resource-poor minority could do so runs counter to common sense.

Anti-Brāhminism falsely portrays Hindu scripture as casteist and hierarchical. It holds Brāhmins as a class guilty for the real or imagined offenses of a few, denying them any consideration of their individual merits. It argues for a mythical Brāhmin privilege that is contradicted by the Hindu worldview based on universal accessibility and transcendence. When historical and scriptural evidence contradict the foundations of Anti-Brāhminism, is it not reasonable to question the underlying assumptions upon which this sort of thinking is based?

Perhaps the time has come to call Anti-Brāhminism for what it really is – a convenient prejudice that has become a politically-correct way by which to perpetrate anti-Hindu bigotry.

Amazing Analysis . Kudos to author for this mind boggling research.

Though I am OBC , but this Brahmin hatred is getting out of hands . Hypocrites are those who condemn caste based discrimination but openly abuse Brahmin caste.